Introduction

Concrete spalling is not caused by freeze-thaw cycles alone; moisture, reinforcement, and quality of materials also influence damage.

You’ll learn how to assess the other contributing factors, recognize the signs early, and apply practical steps to reduce spalling and extend the life of concrete structures.

Key takeaways

- Freeze-thaw is often blamed, but moisture sources and hydration drive spalling.

- Corrosion of steel reinforcement is a major non-freeze spalling trigger.

- Chemical reactions and alkali-silica reactions can mimic spalling signs often.

- Defects in mix design or placement cause early surface scaling and cracking.

- Deicers, salts, and contaminants accelerate deterioration beyond freeze cycles outdoors.

- Early inspection, moisture assessment, and corrosion checks improve diagnosis accuracy.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Key takeaways

- What is concrete spalling? Definitions and visual signs

- Why freeze–thaw cycles are often blamed — and what they actually do

- Corrosion of reinforcement: a primary non‑freeze cause

- Chemical and material reactions that mimic spalling

- Construction and material defects that cause spalling

- Human and environmental factors: deicers, salts, and contamination

- How to inspect and diagnose the root cause

- Repair options, prevention, and long‑term maintenance

- Safety, timing, and when to call a professional

- Common mistakes, warranty considerations, and regional nuances

- Conclusion

- FAQ

What is concrete spalling? Definitions and visual signs

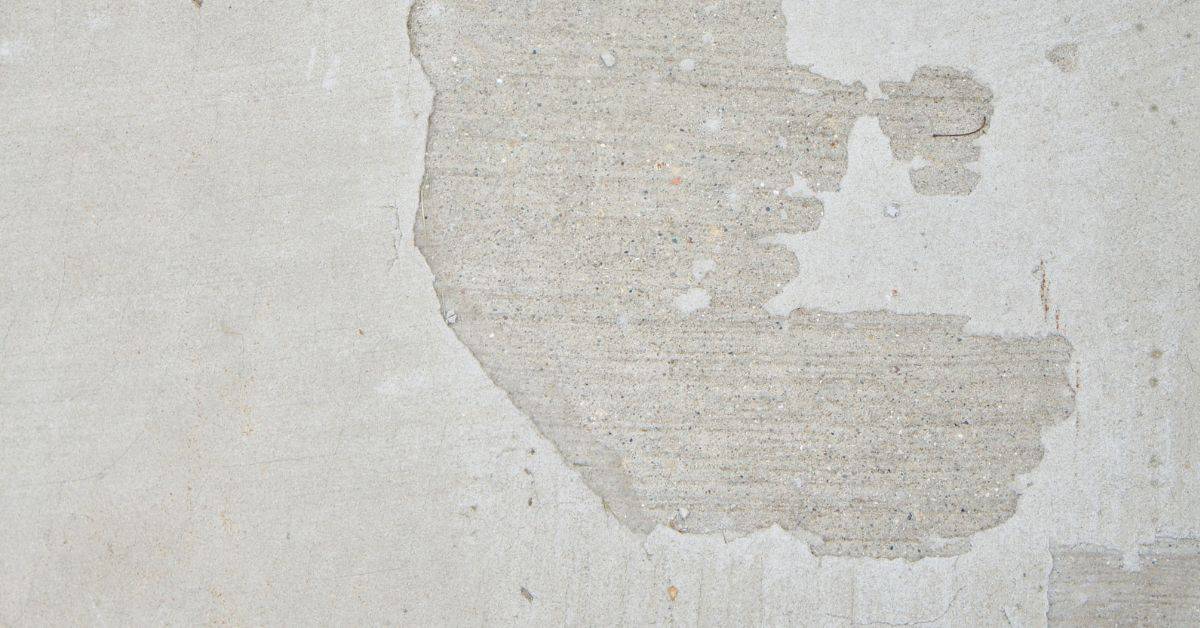

Concrete spalling is the surface failure where the outer skin of a concrete piece flakes, peels, or delaminates, revealing a rough interior and weakening the visible face. It can mimic ordinary finishing issues, but it extends deeper than superficial concerns like scaling or pop-outs. Knowing what to look for helps you separate cosmetic defects from problems that merit attention or professional help.

Quick visual cues and simple at-home tests can guide you: tap the area, observe moisture signatures, and note crack patterns over time. Spalling varies by location—slabs, walls, or decorative surfaces each present differently—and immediate safety steps should always be taken if the damage is extensive or near structural elements.

Pitting, flaking, and scaling — what to look for

Pitting appears as small, deep holes you can feel with a glancing touch; craters may extend deeper than an inch in severe cases. Flaking shows thin layers peeling away, leaving loose granular debris around the base.

Scaling presents larger, plate-like lifts or sheets that separate from the surface. If you can pry a panel with a screwdriver or hammer and it detaches, you’re likely dealing with scaling rather than a shallow finish.

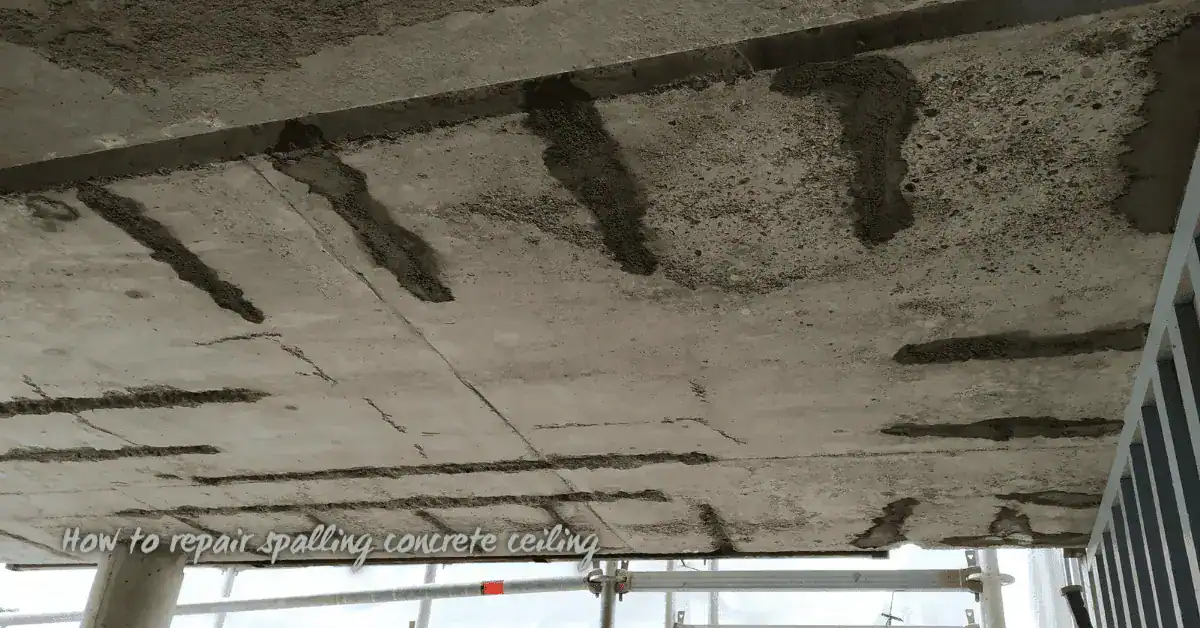

Rebar exposure and delamination indicators

Rust staining along cracks or spalls signals internal steel corrosion. Exposed bars or orange‑brown threads of metal indicate rebar deterioration beneath the skin.

A hollow, drums-like sound when tapping often means a detached layer; solid concrete sounds dense and compact.

Distinguishing cosmetic vs structural spalling

Evaluate depth and spread: shallow chips under 1/4–1/2 inch across a small area are often cosmetic; deep pockets or widespread spalling on load-bearing elements raise structural concerns.

Consider location: decorative surfaces differ from beams, columns, or stair components. When reinforcement or load paths are involved, treat it as structural and seek professional guidance.

Why freeze–thaw cycles are often blamed — and what they actually do

Freeze–thaw damage starts when water infiltrates the concrete pore system, saturates it, and then expands as it freezes. Repeated cycles push on pore walls, widening microcracks and driving surface scaling, spalling, and cracking, especially near the exposed surface that dries and re-wets. In DIY circles, it’s a familiar culprit, but the blame is often overstated or misapplied when other factors mimic or amplify the effect.

Read the moisture environment, exposure to freeze cycles, and the pattern of damage to separate true freeze–thaw failures from other killers. Chloride exposure, poor drainage, inadequate compaction, air-void quality issues, and rebar corrosion can resemble or worsen spalling. Practical prevention hinges on drainage, moisture control, right air-void content, appropriate sealants, and knowing when to call a professional for fixes beyond DIY scope.

The freeze–thaw process in porous concrete

Water migrates into pores and microcracks; when temperatures drop, that water freezes and expands, creating pressure that widens voids and microcracks over many cycles. The damage accumulates gradually, with surface layers peeling or scaling as the weak zones reach the surface.

Key field cues: moisture-rich conditions, seasonal freeze cycles, and damage that begins at edges or areas with poor drainage. Air-entraining admixtures and higher permeability provide escape routes for ice, mitigating pressure. Regular surface sealing and a properly designed mix slow the cycle, while poor drainage or dense, low-porosity mixes accelerate it.

When freeze–thaw is the primary driver — and when it isn’t

Freeze–thaw dominates in environments with repeated wetting and frequent subfreezing temps, especially where drainage is inadequate. In mild/coastal climates or well-drained slabs, it plays a smaller role.

Other factors can overwhelm or mimic freeze–thaw: improper mix design, sulfate attack, heavy traffic, or chronic moisture issues. Look for a combination of water exposure, surface conditions, and structural exposures before attributing spalling to cycles alone.

Corrosion of reinforcement: a primary non‑freeze cause

Corrosion of reinforcement escalates when chloride ions and CO2 breach the concrete’s outer defenses, reaching rebar and disrupting the passive layer that normally slows rust. The ensuing chemistry drives rust growth, which pushes against the surrounding concrete and can trigger spalling near the steel. Early detection through targeted testing keeps repairs practical and affordable.

For field crews, recognizing specific patterns—like rust staining with local breakout near rebar—helps separate corrosion-driven damage from pure freeze–thaw effects. Combine non-destructive tests with selective core checks to confirm active corrosion and map affected zones, guiding durable repairs and long-term protective strategies.

Sources of chlorides: salts, seawater, and deicers

Chlorides reach steel primarily via surface salts, seawater splash, and road deicers that migrate into the concrete pore network. Once chlorides reach the rebar, they undermine the passive film and accelerate corrosion, even at modest moisture levels. Construction practices and adjacent use of deicers can significantly boost ingress if cover and barrier details are weak.

- Non-destructive checks: half-cell potential, covermeter for concrete cover, and rapid chloride tests to flag active ingress.

- Targeted core sampling to confirm corrosion activity and measure chloride concentration with depth.

- Key mitigation: limit exposure to chlorides, improve detailing around high-risk joints, and apply corrosion-inhibiting strategies during repairs.

Carbonation and pH loss — invisible but destructive

Carbonation silently lowers concrete pH as CO2 penetrates the paste, dissolving the protective film on steel and allowing rust to form without chlorides. This process progresses slowly but steadily, especially under poor cover or high-permeability mixes, and can precede visible spalling by years.

- Assess with cover measurements and surface quality checks to gauge protection against CO2 ingress.

- Use targeted cores to verify pH level changes and identify areas where rebar is vulnerable.

- Prevention hinges on robust cover, dense mixes, and protective barriers; repairs may include rebar treatment and corrosion-aware overlays.

Chemical and material reactions that mimic spalling

Alkali–silica reaction (ASR) signs and timeline

ASR shows up as a mottled network of fine, map‑like cracks across the concrete surface. Cracks often follow a web pattern and can be accompanied by a sticky, sometimes brownish gel pushed out of joints or cracks.

The damage develops slowly over months to years as the reactive aggregate expands with alkali and moisture. You’ll see progressive widening of cracks and measurable expansion of slabs or structures rather than sudden flakes coming off like freeze‑thaw damage.

Tip: If the pattern is a web of cracks with gradual bulging or expansion, think ASR. If you see sharp surface scaling after cold spells, that’s more likely freeze‑thaw and not ASR.

Sulfate attack and other chemical deterioration

Sulfate attack comes from soils, groundwater, or contaminated materials. Sulfates react with cement paste to form expansive, weak phases that cause the concrete to soften, crack, and lose surface material.

What you’ll notice is surface powdering, flaking, and progressive loss of paste around aggregates. The concrete becomes crumbly rather than producing intact chunks; rebar corrosion can follow if the paste drops away.

Practical note: Check nearby soils, de‑icing salt exposure, and the origin of aggregates or fill. Removing the source of sulfates and using sulfate‑resistant cement are the usual fixes on the job.

Construction and material defects that cause spalling

Spalling in concrete floors and pavements often stems from material defects that begin at mix design and placement, including incorrect water-cement ratios, inappropriate cement types, poorly chosen air-entraining agents, and non‑optimal aggregate gradation that weaken the surface and underlying matrix. Excessive bleed water and segregation during placement produce a soft laitance layer on the surface, which loses strength under foot traffic, loading, or temperature cycling and becomes a ready site for not‑freeze spalling. Inadequate concrete cover and faulty reinforcement placement expose the surface to abrasion, moisture, and freeze‑thaw stress, while insufficient consolidation creates voids and cracks that initiate spalling under use.

Keeping these factors in check means choosing the right mix, controlling water content, and ensuring proper compaction and curing so the surface develops uniform strength and resists cracking when temperatures swing. On a jobsite, attention to cover, proper consolidation practices, and avoiding premature drying are the practical steps that prevent costly spalling repairs and extend the life of driveways, floors, and concrete slabs. Understanding these defects helps DIYers plan effective timelines, communicate with concrete suppliers, and verify that the finished work will resist not‑freeze stresses rather than crumble after a season of use.

Too much water, weak near‑surface paste, and finishing errors

These are common finishing mistakes that make the top layer soft and prone to flaking. They’re preventable with better mix control and timing.

- Excess mixing water dilutes the cement paste so the surface is weak — use proper slump and add water only when necessary.

- Bleed water left on lets fines rise and weakens the top skin — remove bleed water then finish, don’t burnish wet concrete.

- Early over‑trowelling compresses paste and brings fines up, causing scaling — wait for bleed to disappear and use the right tool at the right time.

- High cement paste content near surface increases shrinkage and cracking — use correctly graded aggregates and avoid paste-heavy mixes for flatwork.

- Finisher inexperience times operations wrong and damages surface — train crews to judge set and follow finishing sequence.

Control the mix, respect bleed and set times, and keep finishing simple. That prevents flaky, scaled surfaces every time.

Inadequate cover and placement mistakes

Too little concrete cover and poor placement let steel corrode and pop the concrete off. Get cover and compaction right from the start.

- Insufficient cover depth exposes rebar to moisture and salt — follow specified cover and use chairs or spacers to hold bars in place.

- Improper bar positioning causes variable cover and weak spots — tie and support reinforcement before placing concrete.

- Poor vibration technique leaves voids around rebar that trap moisture — use internal or external vibration correctly to consolidate concrete around bars.

- Segregation during placement concentrates coarse aggregate away from rebar — place concrete in layers and avoid long drops to keep mix uniform.

- Skipping protective measures lets early exposure start corrosion — cure properly and protect fresh concrete from rapid drying or contamination.

Maintain specified cover, place and consolidate carefully, and secure reinforcement. Those basic steps stop rebar‑related spalling before it starts.

Human and environmental factors: deicers, salts, and contamination

Exposure to deicing salts such as sodium chloride and calcium chloride, along with coastal salt spray and chemical spills, accelerates salt crystallization, osmotic pressure, and accelerated spalling in concrete, especially where protective coatings or sealers are compromised. These contaminants penetrate pores, alter the pore structure, and promote microcracking and delamination, converting seemingly solid surfaces into flaky, weakened layers that fail under freeze–thaw cycles and mechanical wear. In practical terms, roadsides treated with salt, marina edges, and industrial sites with chemical exposure become higher‑risk zones for rapid surface deterioration and hidden corrosion beneath the finish.

DIYers can spot early cues such as salt bloom, white staining, efflorescence, surface cracking from combined freeze–thaw and chemical attack, and corrosion staining that hints at embedded metal corrosion beneath coatings. Understanding these pathways helps you plan prevention: choose sealers and surface treatments rated for salt tolerance, implement better drainage and runoff management, use low-sodium or alternative deicers, and promptly wash away residue before it penetrates and accelerates damage. When indicators escalate to delamination, deep cracks, spalled patches, or suspected structural corrosion, seal and repair promptly, or consult a qualified professional for a thorough corrosion assessment or structural evaluation.

Deicing salts: mechanism and common homeowner mistakes

These are the typical mistakes I see on jobs that speed up spalling. Avoid them and you cut down chloride entry and freeze‑thaw damage.

- Overapplication — pouring on more salt than needed raises chloride levels. Use the minimum effective amount and follow product instructions.

- Late cleanup — leaving salt on concrete lets chlorides soak in. Sweep or rinse surfaces once ice melts to remove residue.

- Using the wrong product — some salts are more corrosive to concrete and reinforcement. Choose low‑chloride or concrete‑safe deicers for walks and patios.

- Poor timing — applying before heavy rain or melt drives salts into pores. Apply when surfaces are dry, then clean up after thaw.

- Ignoring cracks — salts enter and concentrate in cracks, accelerating damage. Seal visible cracks quickly and keep them salt‑free.

Keep salt use targeted and short. Less exposure means fewer chlorides in the slab and a longer concrete life.

Drainage, landscaping, and microclimate effects

Poor drainage and landscaping choices change how wet a slab stays. More water means longer saturation and more opportunity for salts and contaminants to penetrate.

Low spots, compacted soil, clogged gutters, and hardscaping that directs flow toward concrete all keep water against surfaces. That constant wetting raises freeze‑thaw stress and helps dissolved chlorides and chemicals move into the slab.

Spray and splash zones from irrigation or vehicle spray create localized contamination points. Even if the rest of the slab is dry, these zones get repeated wetting and chemical exposure and go bad first.

Fix slopes, keep downspouts aimed away, and avoid planting beds that trap water against concrete. Small grading and drainage fixes cut contamination and slow spalling.

How to inspect and diagnose the root cause

This section walks you through a simple, homeowner‑friendly inspection plan to help you spot where concrete problems start and how they progress over time. It focuses on a quick visual survey, identifying likely root causes from surface clues, and using basic diagnostic tests you can perform without special equipment. It also presents a concise, field‑ready diagnostic workflow you can follow: observation → moisture testing → chloride/pH testing → core sampling if needed, to identify root causes efficiently and safely.

Create a quick visual survey plan that maps crack patterns, joint conditions, spalling extent, staining, and any new movement to distinguish ongoing damage from aging. Identify likely root causes from surface clues—freeze‑thaw damage versus moisture intrusion, poor drainage, improper slab curing, rebar corrosion, or chemical attack—and note which clues point to each cause. Use homeowner‑accessible tests such as a water bead test for permeability, simple moisture meter readings at the slab edge and interior, a tapping or hollow‑sound check to flag delamination, and observations of efflorescence or rust staining as moisture indicators. Assess surrounding conditions—exterior grading, downspout drainage, nearby trees, soil moisture, foundation openings, and signs of soil movement or settlement—to understand how context drives the problem. Finally, document everything with a clear stepsheet: take photos with scale, note location and dimensions, sketch a rough map, and plan a follow‑up test or a professional evaluation if red flags appear.

Step-by-Step Process

This sequence gets you from safe prep through a clear diagnosis and tidy finish. Follow each step in order and pause if something looks unsafe.

- Put on PPE and shut off power or water to the area. Safety first stops accidents and protects your tools. If you smell gas or see major structural damage, stop and call a pro.

- Clear the work area and lay down drop cloths. A clean workspace makes defects easier to spot and keeps debris out of the repair. Quick check: you can move freely and tools are within reach.

- Do a visual sweep for obvious issues: cracks, rust, staining, or mold. Visuals tell you where to focus deeper tests. Right sign: a concentrated problem area to investigate.

- Perform moisture testing at the slab edge and interior with a simple meter to establish baseline moisture levels and identify possible migration paths. Document readings with location and date.

- Conduct a basic permeability check (water bead test) on representative areas to gauge surface infiltration and saturation tendency. Compare against unaffected sections to spot differential seepage.

- Perform sounding and probe checks across the affected zone. These locate delamination and soft spots under the surface. You’ll hear solid versus hollow sounds and feel resistance on the probe.

- Use simple tests (chloride, pH, or half‑cell) where corrosion or contamination is suspected. Test results narrow the likely cause and guide the fix. Immediate check: clear reading or strip change on the test kit.

- If results raise serious questions about rebar integrity or if non‑destructive tests are inconclusive, consider core sampling or professional evaluation. Plan only if practical and within budget, and follow local codes for core work.

- Document findings with photos and notes. This saves time if you bring in a pro or order materials later. You should be able to point to each defect and its likely cause.

- Make minor, temporary fixes if safe and obvious—seal a small crack or tighten a loose fitting. Temporary measures stop damage from worsening until a permanent repair. Confirm the stopgap holds after 24 hours.

- Clean up debris, restore power or water, and re‑inspect the area. Final checks confirm you didn’t miss anything and that temporary fixes are holding. Look for new stains, sounds, or leaks before calling the job done.

Visual, sounding, and probe checks for severity

Start with a clear visual scan. Look for patterns: clustered cracks, repeating rust lines, or a spread of stains. Those patterns tell you whether the problem is local or systemic.

Use a hammer or mallet for sounding. Tap across the surface in a grid. Solid material gives a sharp sound; hollow or delaminated spots give a dull or hollow ring. Mark any hollow notes to map severity.

Follow up with a sharp probe or awl at marked spots. Probe gently to test depth and resistance. Soft, crumbly feel or deep penetration means extensive deterioration. Keep notes of depth and pattern so you can compare areas and prioritize repairs.

When and how to use simple tests (chloride, pH, half‑cell)

Use chloride strips when you suspect salt contamination or deicing chemical damage. Press a dampened concrete sample to a strip or follow the kit directions. A high reading points to increased corrosion risk for embedded steel.

Use pH paper on surfaces where acids or alkalis might be present from spills or efflorescence. Low or very high pH can damage finishes and accelerate breakdown. Match the paper reading to the product limits for adhesives or coatings you plan to use.

Use a basic half‑cell (reference electrode) test if rusting rebar is the concern. It shows relative corrosion activity and helps decide if cathodic protection or rebar repair is needed. These tests are simple but interpret results with reference ranges; if readings are extreme, get a corrosion specialist.

Repair options, prevention, and long‑term maintenance

Repair options for spalling vary by depth, moisture source, and structural impact, so it’s essential to compare epoxy or urethane injections, surface patches, patch mortars, and underpinning or slabjacking, noting when each is appropriate and how they affect long‑term durability, surface finish, and downtime. Plan should weigh crack size, spall depth, moisture origin, potential for recurring damage, cost, and climate factors to choose a method that minimizes future repairs while addressing underlying causes.

Thinking ahead to prevention and maintenance helps shrink recurring damage: focus on moisture control through proper drainage and downspouts, timely sealing, and well‑placed expansion joints, plus climate‑aware concrete mixes and routine re‑sealing. A practical long‑term plan emphasizes regular inspections, documenting cracks and spalls, seasonal moisture checks, and a clear schedule for re‑sealing and escalation to professional remediation when early signs indicate structural or persistent moisture issues.

Localized repairs vs overlays vs replacement — decision guide

Start by diagnosing the cause and the extent of damage. Small spalls, shallow delamination, or isolated cracking point to localized patching. Widespread delamination, large areas of rebar exposure, or structural cracking mean you should consider overlay or replacement.

Overlays work when the substrate is sound but the surface has lost cover or wear. They buy time and restore durability without full demolition. Full slab replacement is the right call when the slab has lost structural capacity, corrosion is advanced, or repairs would be repeatedly needed.

Practical rule: patch small, overlay medium, replace when structure or rebar condition is compromised. Factor in service life desired, downtime, and access for heavy equipment when you decide.

Preventive measures: mix specs, cover, sealers, and drainage fixes

Control the problem at the source. Use a low-permeability mix with appropriate air-entrainment and a higher cementitious content where exposure is severe. Keep reinforcing steel at the proper cover depth during placement.

Sealants and penetrating silanes reduce chloride and moisture entry. Maintain seals and reapply as needed. Fix grading and drainage so water runs away from the slab and downspouts don’t dump at the edge.

Hands-on tip: small landscape tweaks and routine sealing often prevent expensive fixes later. Keep an eye on cracks and ponding after storms.

Typical costs and budgeting ranges

Inspection and testing (visual, sounding, half-cell or lab testing) commonly run a few hundred to a couple thousand dollars depending on scope. Small patch repairs typically range from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars per area, depending on access and prep work.

Overlays vary widely: expect low thousands for minor surface overlays up to tens of thousands for large areas with surface prep. Cathodic protection systems are a bigger investment—often in the mid five-figure range for typical residential to light commercial slabs.

Full slab replacement is the most expensive. Budget from tens to low hundreds of thousands depending on slab size, embedded systems, and site restoration. Get at least two bids and factor a contingency for unknowns.

Safety, timing, and when to call a professional

Key safety is to address any immediate hazards such as loose or hanging concrete, sharp edges, trip risks, and potential water intrusion or electrical hazards in damp areas. Cordon off the area, wear PPE (gloves, eye protection, sturdy footwear, and a mask if dusty), and avoid leaning on or vibrating the wall or slab; monitor for active cracking or movement and seek inspection if cracking worsens after loading, bulging, or signs of differential settlement appear. If you notice substantial or growing cracks, new spalling after attempts at repair, bulging concrete, or doors and windows sticking, call a structural engineer or foundation specialist right away, otherwise plan a professional assessment within a few days. Concrete decision triggers to pause DIY work and escalate to a professional include: reinforcing steel exposed or visibly rusting, cracks wider than about 1/4 inch (6 mm) or that are rapidly widening, visible movement or differential settlement, bulging or leaning sections, hollow sounds or crumbling when tapped, ongoing water intrusion or moisture-related deterioration, or any signs that a load-bearing element may be compromised. If any of these are present, avoid further DIY fixes beyond temporary safety measures and contact a professional promptly.

This guidance helps you balance DIY safety with clear thresholds so you can protect people and avoid escalating damage. Collecting photos with dates, a simple timeline of spalling, moisture history, and notes on drainage or landscaping changes gives the pro a quick, accurate picture, saving time and money. Understanding why timely professional input matters—rather than assuming quick fixes will suffice—helps prevent hidden issues from progressing and ensures proper stabilization and safety before further work or occupancy.

Immediate safety actions for homeowners and contractors

If you spot a hazard — collapsed formwork, exposed or bent rebar, or unstable soil — clear the area and keep everyone back. Rope off the zone, post a visible sign, and restrict access until a competent person assesses it. Safety comes before fixes.

If a structural element looks like it might move, don’t try to jack or pry it yourself. Use temporary shoring only if you or your crew are trained and have appropriate materials. Otherwise, stabilize with simple blocking and call for professional help.

Avoid touching or stepping on disturbed rebar. It’s sharp and can shift underfoot, causing injury and creating liability. Wear gloves, boots, and eye protection if you must get near the area, and document conditions with photos for the contractor or engineer who will take over.

Hiring a contractor or structural engineer — checklist and questions to ask

Start by asking for proof of licensing, insurance, and references from similar jobs. Ask whether they carry professional liability and workers’ comp. Request a timeline and an outline of the work they’ll do — inspections, temporary shoring, and permanent repairs.

On the call, ask specific questions: Who will conduct the site assessment? Will you get a written inspection report with photos and recommended repairs? How will they protect the site while work is planned? A good pro will explain the steps and show prior reports.

When they arrive, expect a concise report with findings, risk level, recommended fixes, and an estimate. Require a written scope of work before any repairs start and keep copies of all permits and photos. That paperwork protects you and speeds up decisions on tougher fixes.

Common mistakes, warranty considerations, and regional nuances

Repairs should target root causes, not just patch surface spalls, because moisture intrusion, poor drainage, and hidden rebar corrosion drive recurrence and undermine pavement, wall, or slab performance. Patching without addressing these factors invites repeated failures and higher long-term costs, since the underlying moisture problem can worsen and rebar degradation can compromise structural capacity. Regional climate, material variables, and warranty terms should guide material choices, installation methods, and documentation expectations, ensuring that recommendations fit local conditions and insurer or manufacturer requirements.

Rebar treatment is critical when embedded steel shows signs of damage; include proper cleaning, compatible coatings, and, if needed, selective replacement to preserve structural integrity and prevent hidden deficiencies from progressing. Regional factors like freeze-thaw severity, de-icing salts, humidity, soil type, and drainage shape repair strategy, selection of patch materials, and anticipated durability under local conditions. Maintain a clear plan with essential records (material specs, photos, moisture tests, before/after inspections), a practical inspection routine, moisture and chloride testing, and a staged repair roadmap that aligns with warranty coverage and reasonable homeowner expectations.

Frequent contractor/homeowner errors and how to avoid them

These are the typical screw‑ups I see on jobs — the ones that come back to bite you. Know them and stop repeating them.

- Cosmetic patching only — Covering cracks with surface skim coats hides the problem. Open it up, find the cause, and fix the substrate before you patch.

- Wrong material choice — Using the wrong mix, sealer, or reinforcement invites failure. Match materials to the job and follow manufacturer specs.

- Poor rebar treatment — Leaving corroded steel or installing without proper cover causes spalling. Clean, repair, or replace rebar and maintain correct concrete cover.

- Skipping prep work — Slapping new material over dirt or laitance won’t bond. Remove contaminants and profile the surface for adhesion.

- Ignoring drainage — Water pooling accelerates damage. Grade for runoff and install drains or scuppers where needed.

Fix the root cause, not just the look. It takes a bit more work up front but saves time and money later.

Climate and regional notes: when freeze‑thaw is minimal but other causes dominate

Not every region fails from freeze‑thaw. In warm or dry climates different enemies show up. Know what your area throws at concrete and plan accordingly.

Coastal zones often suffer from chloride-induced corrosion. Salt sprays and sea breezes speed up rebar rust. Use higher covers, corrosion-resistant rebar or coatings, and select mixes with low permeability. Don’t rely on standard inland specs there.

Some inland areas have reactive aggregates that cause alkali-silica reaction (ASR). That leads to map cracking over years. Use low-alkali cement, SCMs like fly ash or slag, and test local aggregates before large pours.

Sulfate soils and high ground salts are another regional problem. Where sulfates are present, choose sulfate-resistant cement and proper drainage. In arid zones, salt accumulation and thermal cycling matter more than freeze, so focus on sealers and control joints sized for movement.

Conclusion

The bottom line: concrete spalling isn’t just about cold weather. It’s a wake‑up call that failure can come from more than one source, and ignoring the real cause invites bigger damage and higher costs.

Take a practical, step‑by‑step read of the surface, then do this in order: inspect for visible signs, note whether corrosion, chemical reactions, or construction flaws look likely, check for deicers or contamination that could be at fault, test a small area to confirm the diagnosis, review repair options that fit the root cause, and plan a long‑term maintenance and moisture control approach. Start small, document what you find, and use the right repair method for the specific issue you uncover. Safety first governs every move, from PPE to working in proper conditions and not rushing repairs.

A few common mistakes to avoid: never patch without identifying the true cause, don’t rely on a quick cosmetic fix that ignores moisture or reinforcing steel, and don’t mix or apply repair products beyond their intended use. If you’re unsure about corrosion, underlying delamination, or certifications and warranties, don’t push past safe limits—get the right material and method for the actual problem and follow manufacturer directions to the letter.

When in doubt about the root cause, timing, or repair scope, call a professional sooner rather than later. With careful diagnosis and deliberate, safety‑driven work, you can protect durability, appearance, and future maintenance efforts—and keep the project moving without costly surprises.

FAQ

What causes concrete spalling besides freeze-thaw cycles?

Freeze-thaw is a big factor, but moisture in the concrete, poor mix, and improper curing matter just as much. When water gets trapped, it expands and pushes the surface apart. Bad surface finishes and coatings can trap that moisture too.

Why does moisture near the surface matter most?

Moisture at the top dries slower and freezes first. That push from the freezing water starts peeling the finish and the top layer. If water stays there long term, the damage keeps growing.

Are bad drainage and leaks making spalling worse?

Yes. Wet basements, dripping leaks, and poor grading soak the slab. Water sitting next to concrete weakens the bond and speeds up the peeling process. Fix the leak and fix the grade to stop the cycle.

What should I do now to prevent more spalling?

Seal cracks and control moisture with proper flashing and drainage. Use a breathable, compatible sealer on old surfaces if you must, and fix the source of water first. Don’t babysit the problem with quick fixes that trap moisture.